Profile

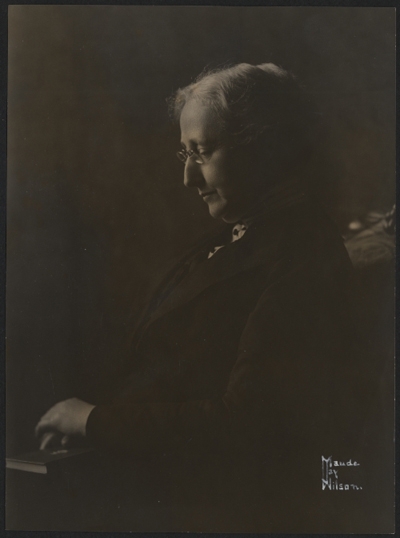

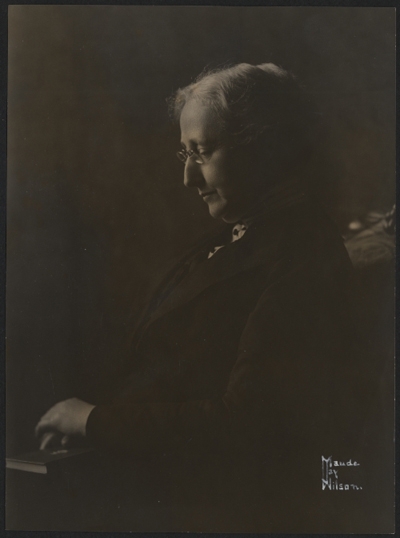

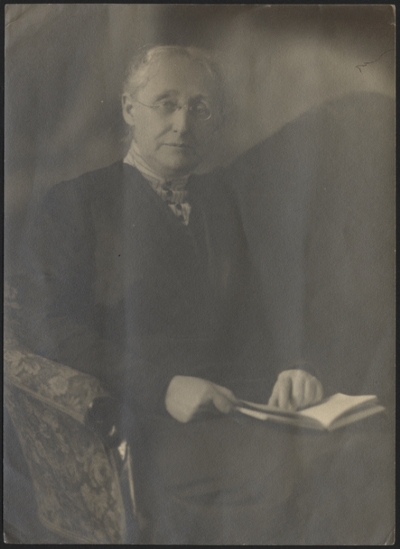

Lillien Jane Martin

Birth:

1851

Death:

1943

Training Location(s):

PhD, Psychological Institute of Bonn (1913)

MA, Psychological Institute of Bonn (1913)

AB, Vassar College (1880)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Indianapolis High School (1880-1889)

San Francisco Girls High School (1889-1894)

University of Gottingen (1894-1898)

Stanford University (1899-1916)

Mount Zion Hospital (1920-1943)

Other Media:

Archives

Lillien Martin Photograph Collection, Stanford Historical Photograph Collection

Lillien Jane Martin Typescripts, Stanford University Library

Career Focus:

Experimental psychology; applied psychology; child psychology; education; aesthetics; perception; old age.

Biography

Lillie Jane Martin was born on July 7, 1851 in Olean, New York. Several years later she changed her name to Lillien, a name she borrowed from a relative because she liked it better than her own. Her mother, Lydia Hawes Martin, encouraged her daughter from an early age to pursue an education. Martin’s father, Russell Martin, was a college-educated merchant who after Martin was born abandoned the family. Martin was thus forced to help care for her three younger siblings and work menial jobs to help support her family. At her own insistence, Martin was enrolled into the Olean Academy at four years of age. Following her graduation at 16, she and her family moved to Racine, Wisconsin. In Racine, Martin accepted a position at Kemper Hall, an Episcopal girl’s school in Kenosha.

Martin admired her mother for having a positive attitude, being strong-willed and self-sufficient. She credited her mother for much of her success, and claimed it was at her mother’s side that she learned to be responsible, industrious, and to value education. Martin identified strongly with her mother and acquired a negative attitude towards marriage. Despite having numerous romantic relationships, she chose to never marry. She identified with “women-in-general” and represented many feminist organizations and causes.

Martin continued with her education throughout her entire life. She detested esoteric learning and preferred education that focused on pragmatic knowledge. Her goal was to earn enough money to attend college. To this end, she moved to Omaha, Nebraska, where she taught at another Episcopal school. It was not until 1875 that she was able to afford college.

Martin was accepted into Cornell University; however her mother did not allow her to attend. Instead, Martin entered Vassar College on a scholarship. She studied at Vassar from 1875 to 1880 and majored in natural sciences. Her good grades and strong work ethic earned her the nickname “little owl.” Martin was not only a good student, but she had several years’ experience teaching. It is reported that Martin helped tutor her classmates gratis. Following her graduation from Vassar in 1880, she held a high school teaching position in Indianapolis, Indiana where she taught students physics and chemistry. She held this position for nine years, during which time she started her custom of joining summer courses at various midwestern and eastern universities.

In the course of her tenure at Indianapolis, Martin published scientific articles and was invited to give lectures at education associations. In 1889, after delivering a speech at an educational convention in San Francisco, Martin was offered the position of vice principal and head of the science department at a Girls’ High School in San Francisco. She accepted the position and moved to the Bay area. She loved San Francisco and made it her home for the next fifty-four years. However, Martin still wished to continue her education. In 1894, she resigned from her teaching position (her first “retirement”) and returned to academia.

Martin studied psychology at the University of Gottingen, in Germany. Although the university was not keen on accepting women, Martin nonetheless became the second female student to study in the program. At Gottingen, Martin trained as an experimental psychologist and was later introduced to G. E. Müller. Martin eventually became Müller’s assistant, and together they conducted research on the psychophysics of lifted weights. Their work was published in the book; Zur Analyse der Unterschiedsemfindlichkeit (1899), and is still considered a classic in psychophysics.

From 1894 to 1898, Martin remained at Gottingen. She conducted research on a great diversity of subjects, including aesthetics, perception, imageless thought, and humor. For fifteen years, she published extensively in German and returned to Germany every summer to study and conduct research.

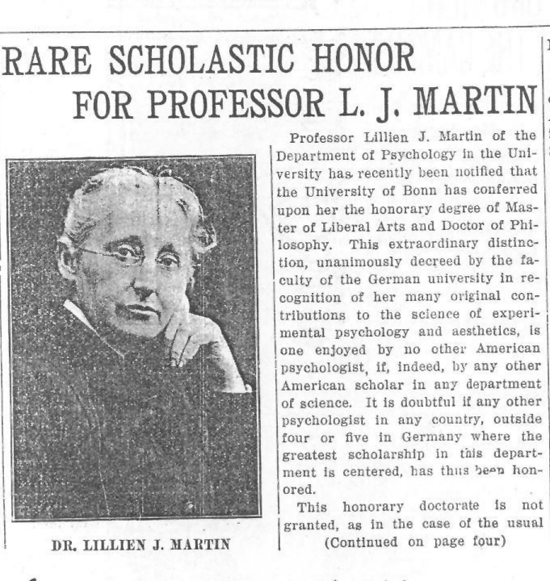

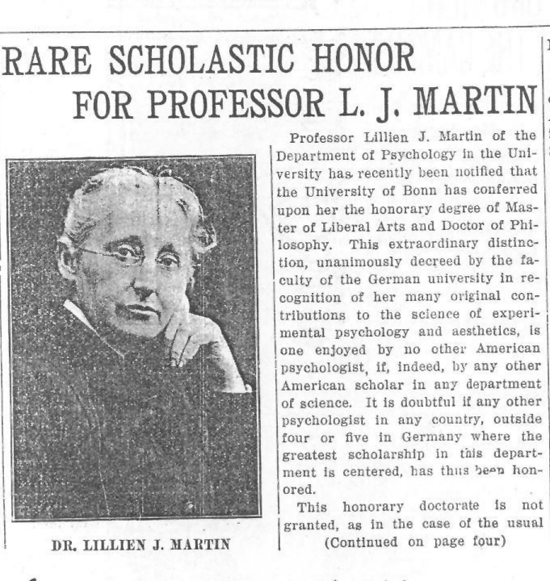

Martin never received an earned Ph.D. However, in 1913, honoring her works based on the theories of Oswald Külpe, the Psychological Institute of Bonn awarded Martin an honorary Master of Liberal Arts and Doctor of Philosophy. This marked the first time an honorary doctorate was awarded to an American psychologist.

In 1899, Martin received a telegram from David Starr Jordan, then-President of Stanford University, inviting her to join Professor Frank Angell in the psychology faculty at Stanford. Martin was an extraordinary teacher, very conscientious and personally concerned over the development of her students. Her excellent administration skills and her well-developed organizational ability led to Angell’s entrusting administrative tasks to Martin. Moreover, when Angell made his periodic pilgrimages to Germany, Martin was appointed acting head of the department. She was the first woman to be appointed department head at Stanford.

Martin began her career at Stanford as an assistant professor in 1899, before being promoted to associate professor in 1909 and to full professor in 1911. She was a popular host in the Palo Alto area, although she tended to associate most frequently and most closely with women. In 1916, at the age of sixty-five, Martin was “retired” from Stanford and awarded the distinction of professor emeritus.

In 1920, four years after Martin had been retired by Stanford, she founded the first mental hygiene clinic in the world for “normal preschoolers.” The clinic was in Mount Zion Hospital, San Francisco, where Martin became head of the mental hygiene and Polyclinic. During this period, Martin spent her afternoons in her own private office, where she had set up practice as a clinical psychologist. With Martin’s clinic running smoothly, she retired from Mount Zion in 1943.

Throughout the 1930s, Martin was one of the most well-known woman psychologists in America. She was recognized for her contributions to clinical psychology and public service; however she also conducted exciting research on projection. In her 1915 article; An Experimental Contribution to the Investigation of the Subconscious, Martin confirmed that subconscious thinking resulted in faster response times than conscious thought and that subconscious mental activity varied in richness of content in different individuals. Martin also conducted research in psychophysics and aesthetics. In her 1906 article, Experimental Study of Fechner’s Principles of Aesthetics, Martin explained Gustav Theodor Fechner’s formulas of aesthetics and examined their validity. The article was later criticized by E. B. Titchener in Professor Martin on the Perky Experiments (1913). Titchener argued that Martin’s analysis of Fechner’s formulas were not relevant and questioned her methods of testing.

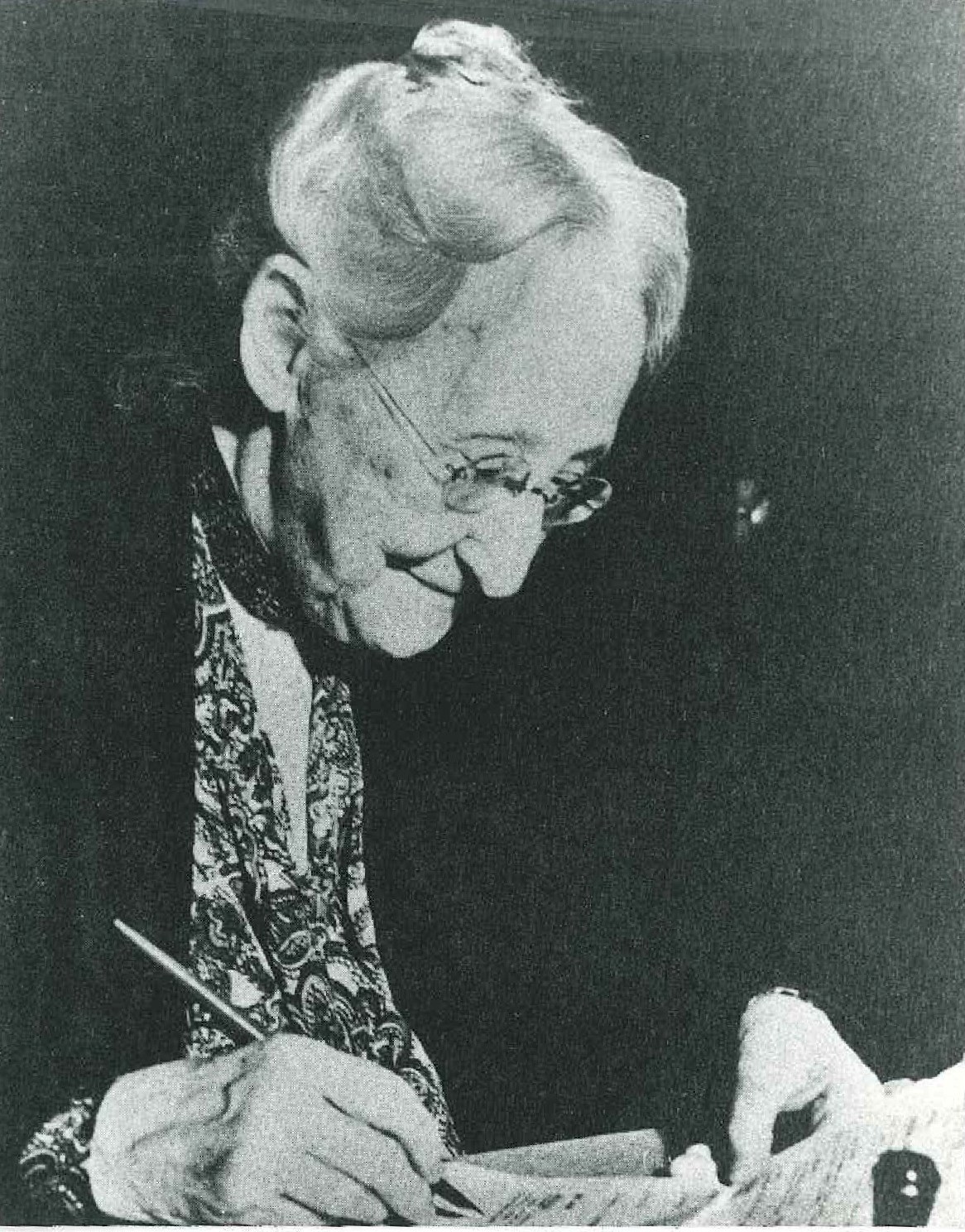

In 1929, Martin founded the Old Age Center, the first counseling center ever established for senior citizens. Here she attempted to implement a system that promoted healthy living and productivity to combat the effects of old age. She became an international authority on gerontology, and in 1937 she opened a farm in Alameda Country. The farm was reported to “give employment and restore self-confidence to a group of elderly men.” The Old Age Center and the farm were extremely successful and occupied her time until her death from bronchopneumonia at the age of 92, in 1943.

by Matthew Pelcowitz (2012)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Lillien Jane Martin

Martin, L. J. (1906). An experimental study of Fechner's principles of asesthetics. Psychological Review, 13, 142-219.

Martin, L. J., & Titchener, B. E. (1913). Professor Martin on the perky experiments. The American Journal of Psychology, 24, 579-579.

Martin, L. J. (1915). An experimental contribution to the investigation of the subconscious. Psychological Review, 22, 251-258.

Martin, L. J. (1917). Mental hygiene and the importance of investigating it. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1, 67-70.

Martin, L. J. (1920). Mental hygiene: Two years’ experience as a clinical psychologist. Baltimore, MD: Warwick & York.

Martin, L. J. (1927). Round the world with a psychologist. San Francisco: J. W. Stacey.

Martin, L. J., & Müller, G., E. (1899). Zur analyse der unterschiedsemfindlichkeit. Germany: Nabu Press.

About Lillien Jane Martin

deFord, M. A. (1948). Psychologist unretired: The life pattern of Lillien J. Martin. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Fenton, N. (1943). Lillien Jane Martin, 1851-1943. Psychological Review, 50, 440-442.

Merrill, A. M. (1943). Lillien Jane Martin: 1851-1943. The American Journal of Psychology, 56, 453-454.

Stevens, G., & Gardner, S. (1982). Contributions to the history of psychology: XXXI. Life as an experiment: The long career of Lillien Jane Martin (1851–1942). Psychological Reports, 51, 579-590.

Williams, J. H. (1942). Lillien Jane Martin: Consultant unretired. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 6, 262-264.

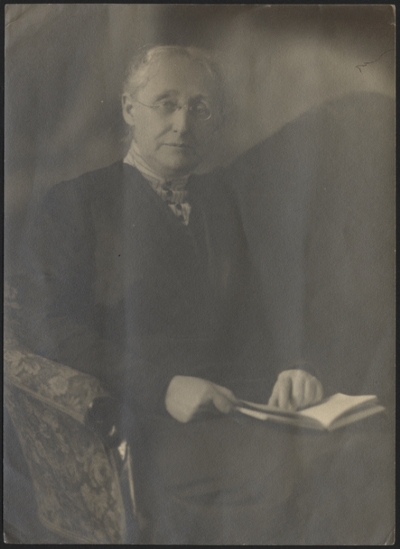

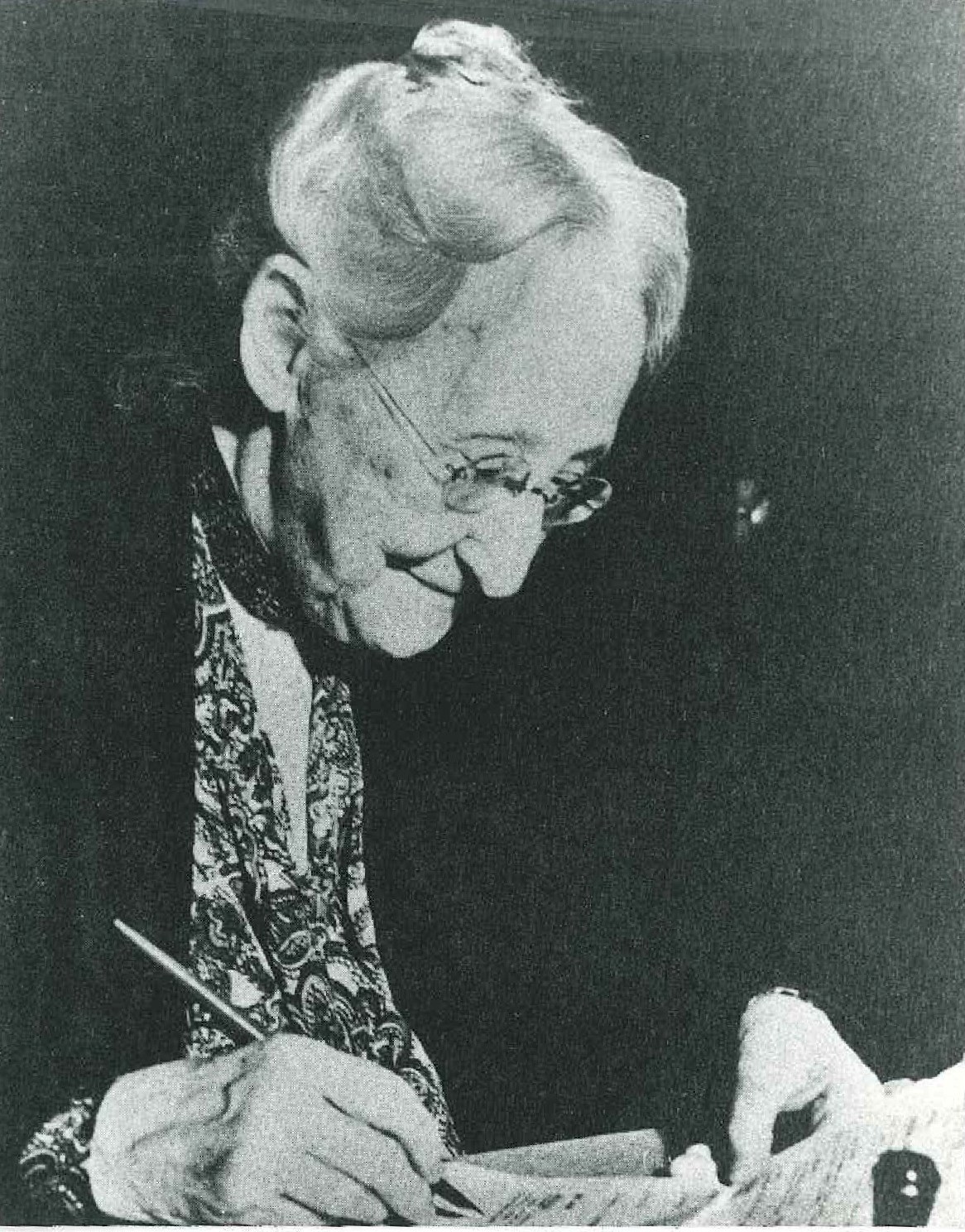

Photo Gallery

Lillien Jane Martin

Birth:

1851

Death:

1943

Training Location(s):

PhD, Psychological Institute of Bonn (1913)

MA, Psychological Institute of Bonn (1913)

AB, Vassar College (1880)

Primary Affiliation(s):

Indianapolis High School (1880-1889)

San Francisco Girls High School (1889-1894)

University of Gottingen (1894-1898)

Stanford University (1899-1916)

Mount Zion Hospital (1920-1943)

Other Media:

Archives

Lillien Martin Photograph Collection, Stanford Historical Photograph Collection

Lillien Jane Martin Typescripts, Stanford University Library

Career Focus:

Experimental psychology; applied psychology; child psychology; education; aesthetics; perception; old age.

Biography

Lillie Jane Martin was born on July 7, 1851 in Olean, New York. Several years later she changed her name to Lillien, a name she borrowed from a relative because she liked it better than her own. Her mother, Lydia Hawes Martin, encouraged her daughter from an early age to pursue an education. Martin’s father, Russell Martin, was a college-educated merchant who after Martin was born abandoned the family. Martin was thus forced to help care for her three younger siblings and work menial jobs to help support her family. At her own insistence, Martin was enrolled into the Olean Academy at four years of age. Following her graduation at 16, she and her family moved to Racine, Wisconsin. In Racine, Martin accepted a position at Kemper Hall, an Episcopal girl’s school in Kenosha.

Martin admired her mother for having a positive attitude, being strong-willed and self-sufficient. She credited her mother for much of her success, and claimed it was at her mother’s side that she learned to be responsible, industrious, and to value education. Martin identified strongly with her mother and acquired a negative attitude towards marriage. Despite having numerous romantic relationships, she chose to never marry. She identified with “women-in-general” and represented many feminist organizations and causes.

Martin continued with her education throughout her entire life. She detested esoteric learning and preferred education that focused on pragmatic knowledge. Her goal was to earn enough money to attend college. To this end, she moved to Omaha, Nebraska, where she taught at another Episcopal school. It was not until 1875 that she was able to afford college.

Martin was accepted into Cornell University; however her mother did not allow her to attend. Instead, Martin entered Vassar College on a scholarship. She studied at Vassar from 1875 to 1880 and majored in natural sciences. Her good grades and strong work ethic earned her the nickname “little owl.” Martin was not only a good student, but she had several years’ experience teaching. It is reported that Martin helped tutor her classmates gratis. Following her graduation from Vassar in 1880, she held a high school teaching position in Indianapolis, Indiana where she taught students physics and chemistry. She held this position for nine years, during which time she started her custom of joining summer courses at various midwestern and eastern universities.

In the course of her tenure at Indianapolis, Martin published scientific articles and was invited to give lectures at education associations. In 1889, after delivering a speech at an educational convention in San Francisco, Martin was offered the position of vice principal and head of the science department at a Girls’ High School in San Francisco. She accepted the position and moved to the Bay area. She loved San Francisco and made it her home for the next fifty-four years. However, Martin still wished to continue her education. In 1894, she resigned from her teaching position (her first “retirement”) and returned to academia.

Martin studied psychology at the University of Gottingen, in Germany. Although the university was not keen on accepting women, Martin nonetheless became the second female student to study in the program. At Gottingen, Martin trained as an experimental psychologist and was later introduced to G. E. Müller. Martin eventually became Müller’s assistant, and together they conducted research on the psychophysics of lifted weights. Their work was published in the book; Zur Analyse der Unterschiedsemfindlichkeit (1899), and is still considered a classic in psychophysics.

From 1894 to 1898, Martin remained at Gottingen. She conducted research on a great diversity of subjects, including aesthetics, perception, imageless thought, and humor. For fifteen years, she published extensively in German and returned to Germany every summer to study and conduct research.

Martin never received an earned Ph.D. However, in 1913, honoring her works based on the theories of Oswald Külpe, the Psychological Institute of Bonn awarded Martin an honorary Master of Liberal Arts and Doctor of Philosophy. This marked the first time an honorary doctorate was awarded to an American psychologist.

In 1899, Martin received a telegram from David Starr Jordan, then-President of Stanford University, inviting her to join Professor Frank Angell in the psychology faculty at Stanford. Martin was an extraordinary teacher, very conscientious and personally concerned over the development of her students. Her excellent administration skills and her well-developed organizational ability led to Angell’s entrusting administrative tasks to Martin. Moreover, when Angell made his periodic pilgrimages to Germany, Martin was appointed acting head of the department. She was the first woman to be appointed department head at Stanford.

Martin began her career at Stanford as an assistant professor in 1899, before being promoted to associate professor in 1909 and to full professor in 1911. She was a popular host in the Palo Alto area, although she tended to associate most frequently and most closely with women. In 1916, at the age of sixty-five, Martin was “retired” from Stanford and awarded the distinction of professor emeritus.

In 1920, four years after Martin had been retired by Stanford, she founded the first mental hygiene clinic in the world for “normal preschoolers.” The clinic was in Mount Zion Hospital, San Francisco, where Martin became head of the mental hygiene and Polyclinic. During this period, Martin spent her afternoons in her own private office, where she had set up practice as a clinical psychologist. With Martin’s clinic running smoothly, she retired from Mount Zion in 1943.

Throughout the 1930s, Martin was one of the most well-known woman psychologists in America. She was recognized for her contributions to clinical psychology and public service; however she also conducted exciting research on projection. In her 1915 article; An Experimental Contribution to the Investigation of the Subconscious, Martin confirmed that subconscious thinking resulted in faster response times than conscious thought and that subconscious mental activity varied in richness of content in different individuals. Martin also conducted research in psychophysics and aesthetics. In her 1906 article, Experimental Study of Fechner’s Principles of Aesthetics, Martin explained Gustav Theodor Fechner’s formulas of aesthetics and examined their validity. The article was later criticized by E. B. Titchener in Professor Martin on the Perky Experiments (1913). Titchener argued that Martin’s analysis of Fechner’s formulas were not relevant and questioned her methods of testing.

In 1929, Martin founded the Old Age Center, the first counseling center ever established for senior citizens. Here she attempted to implement a system that promoted healthy living and productivity to combat the effects of old age. She became an international authority on gerontology, and in 1937 she opened a farm in Alameda Country. The farm was reported to “give employment and restore self-confidence to a group of elderly men.” The Old Age Center and the farm were extremely successful and occupied her time until her death from bronchopneumonia at the age of 92, in 1943.

by Matthew Pelcowitz (2012)

To cite this article, see Credits

Selected Works

By Lillien Jane Martin

Martin, L. J. (1906). An experimental study of Fechner's principles of asesthetics. Psychological Review, 13, 142-219.

Martin, L. J., & Titchener, B. E. (1913). Professor Martin on the perky experiments. The American Journal of Psychology, 24, 579-579.

Martin, L. J. (1915). An experimental contribution to the investigation of the subconscious. Psychological Review, 22, 251-258.

Martin, L. J. (1917). Mental hygiene and the importance of investigating it. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1, 67-70.

Martin, L. J. (1920). Mental hygiene: Two years’ experience as a clinical psychologist. Baltimore, MD: Warwick & York.

Martin, L. J. (1927). Round the world with a psychologist. San Francisco: J. W. Stacey.

Martin, L. J., & Müller, G., E. (1899). Zur analyse der unterschiedsemfindlichkeit. Germany: Nabu Press.

About Lillien Jane Martin

deFord, M. A. (1948). Psychologist unretired: The life pattern of Lillien J. Martin. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Fenton, N. (1943). Lillien Jane Martin, 1851-1943. Psychological Review, 50, 440-442.

Merrill, A. M. (1943). Lillien Jane Martin: 1851-1943. The American Journal of Psychology, 56, 453-454.

Stevens, G., & Gardner, S. (1982). Contributions to the history of psychology: XXXI. Life as an experiment: The long career of Lillien Jane Martin (1851–1942). Psychological Reports, 51, 579-590.

Williams, J. H. (1942). Lillien Jane Martin: Consultant unretired. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 6, 262-264.